Bilingual Black Hole:

What Canada’s Registry Data Could Reveal about Access to Language Concordant Care

By Nimrit Kenth | December, 2025

Imagine needing urgent medical care but not being able to speak the language of the healthcare practitioner. Imagine having access to a database where you see a practitioner possibly speaks your language, but upon arrival you find they do not.

For many Francophones outside of Quebec and English-speaking minorities within Quebec, this is a daily reality. Despite Canada’s commitments to bilingualism and official language rights, notably the recent developments to the federal Official Languages Act, only a fraction of these populations can readily access care in their preferred language. The invisible language gap in Canada’s health workforce is exacerbated by an invisible data gap; federal legislation does not seem to trickle down to regional regulatory authorities: the bodies that oversee licensing of health practitioners.

Overview of Study Results

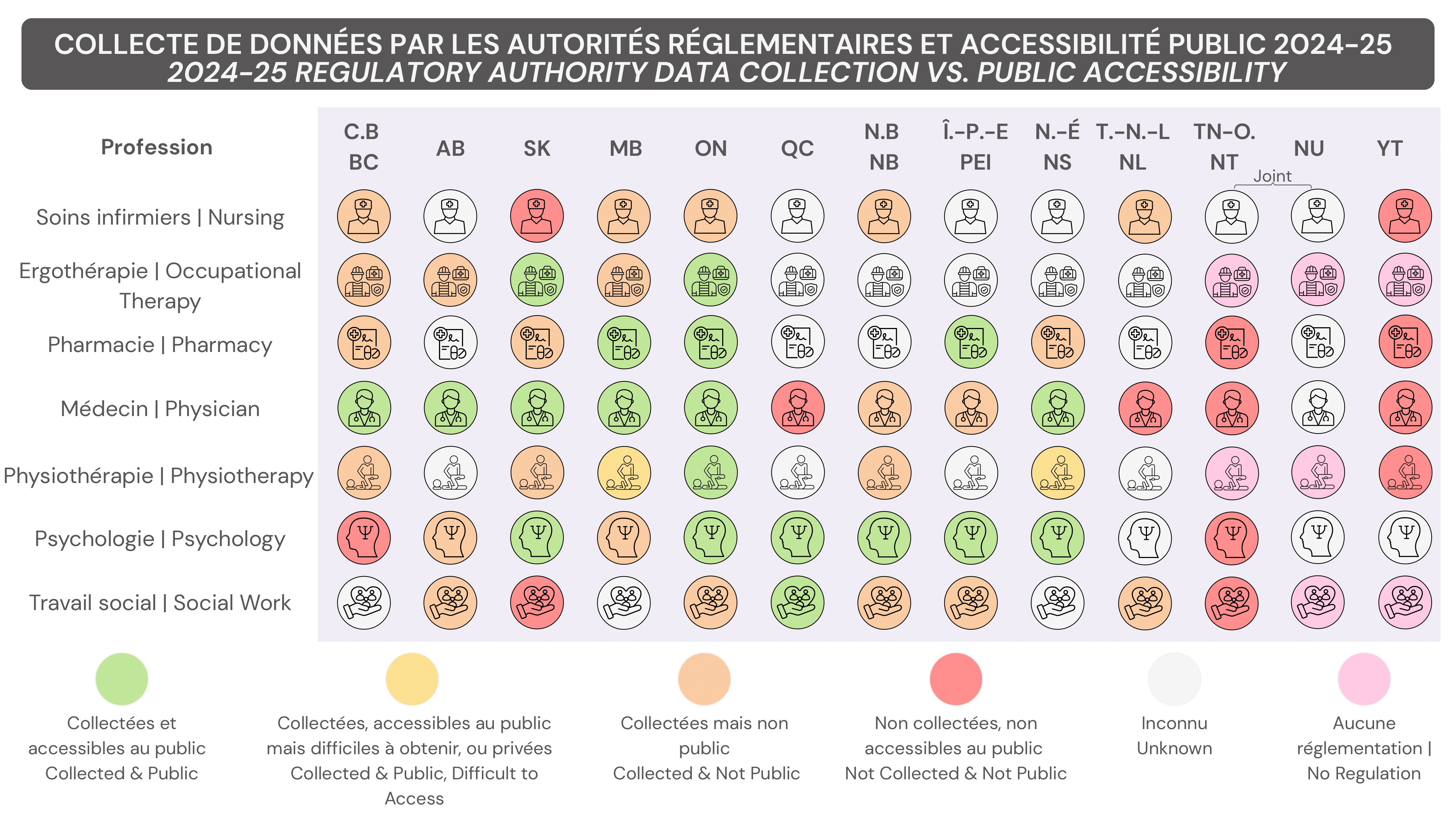

In 2024–25 we underwent a research project examining linguistic data collection across seven of Canada's regulated health professions, through regional regulatory authorities. This was a follow-up to a study in 2017, and the comparison from both studies revealed a troubling pattern. In 2024-25 while 51.8% of regulatory authorities now collect linguistic information on health professionals, only 25.3% make that data publicly available. Without public access, these data cannot support system planning, workforce forecasting, or equity-focused policy development, leaving the communities most needing language-concordant care underserved.

The core problem: no consistent legislative requirement exists. As a result, collection remains patchy and inconsistent across professions and jurisdictions, while many regulators cite privacy legislation as a barrier, often misinterpreting rules that do not explicitly prohibit such collection.

Why Accessible Data Matters?

Publicly accessible linguistic data is not a technical detail; it is the difference between guessing and guaranteeing that French- and English-speaking minorities can actually receive care in their language. Without clear information on who offers services in which language, health systems cannot plan where to recruit and where to train or fund bilingual positions, leaving minority communities to navigate care through chance, personal networks, or trial and error.

When linguistic data stay locked inside regulatory databases, or are collected with vague, inconsistent questions, patients cannot reliably use them to find language concordant practitioners, and policymakers cannot see where rights promised in law are failing in practice. Transparent, standardized and accessible data is therefore not just an equity tool; it is an accountability mechanism that allows communities, advocates, and researchers to hold authorities to their commitments to prioritise public interest.

Data gaps/ lack of accessibility

Data gaps and lack of accessibility sit at the heart of the problem. Across provinces and professions, there is no consistent requirement to collect linguistic data, and even when regulators do capture information, they use different questions, categories, and definitions, making it difficult to compare or aggregate. Words matter: asking whether a practitioner "can" speak French is not the same as asking whether they "currently offer services in French," and those nuances directly shape what we think the system can deliver.

A Foundation for Change

The path forward requires three coordinated shifts: 1) standardized linguistic indicators that capture actual service delivery, ideally beyond self-reported ability, 2) legislative clarity mandating collection for public dissemination, and 3) data accessibility that enables researchers, planners, and policymakers to align workforce capacity with community need.

Ultimately, equitable access to healthcare starts with equitable access to data supporting that care. Ontario's inclusion of linguistic data in its health workforce minimum data standard demonstrates what is possible: more systematic collection, better data quality, enabling greater public accessibility. Nationally, the Canadian Institute of Health Information has included linguistic ability in their 2022 data standard. Société Santé en français and the Canadian Health Workforce Network are advancing work on integrating linguistic data through data standards through research, advocacy, and data development.

Without knowing where linguistic gaps exist, we cannot design systems that truly serve all Canadians. The data to fix this already exists in provincial registries; we need only the mandate, infrastructure, and political will to use it.